The Snow Queen was an original fairy tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen in 1844. It tells the story of Kai being kidnapped by the Snow Queen and Gerda’s journey to rescue him. It is a coming of age story, but it also deals with faith and science, good and evil, and some of its elements are loaded with allegorical meaning.

Stories, however, don’t come out of the blue. The story type Andersen uses was already known to the Ancient Greeks, and some of the characteristics of the Snow Queen herself can be traced back more than a thousand years to the times of the heathen religion. At the same time, other authors have used Andersen’s tale as inspiration for their own stories, from Victorian author George MacDonald to C. S. Lewis Narnia’s Chronicles. And, of course, Disney’s Frozen film, which has revived the interest of Andersen’s Snow Queen in recent years.

The Snow Queen, Skaði, and the Norse myths

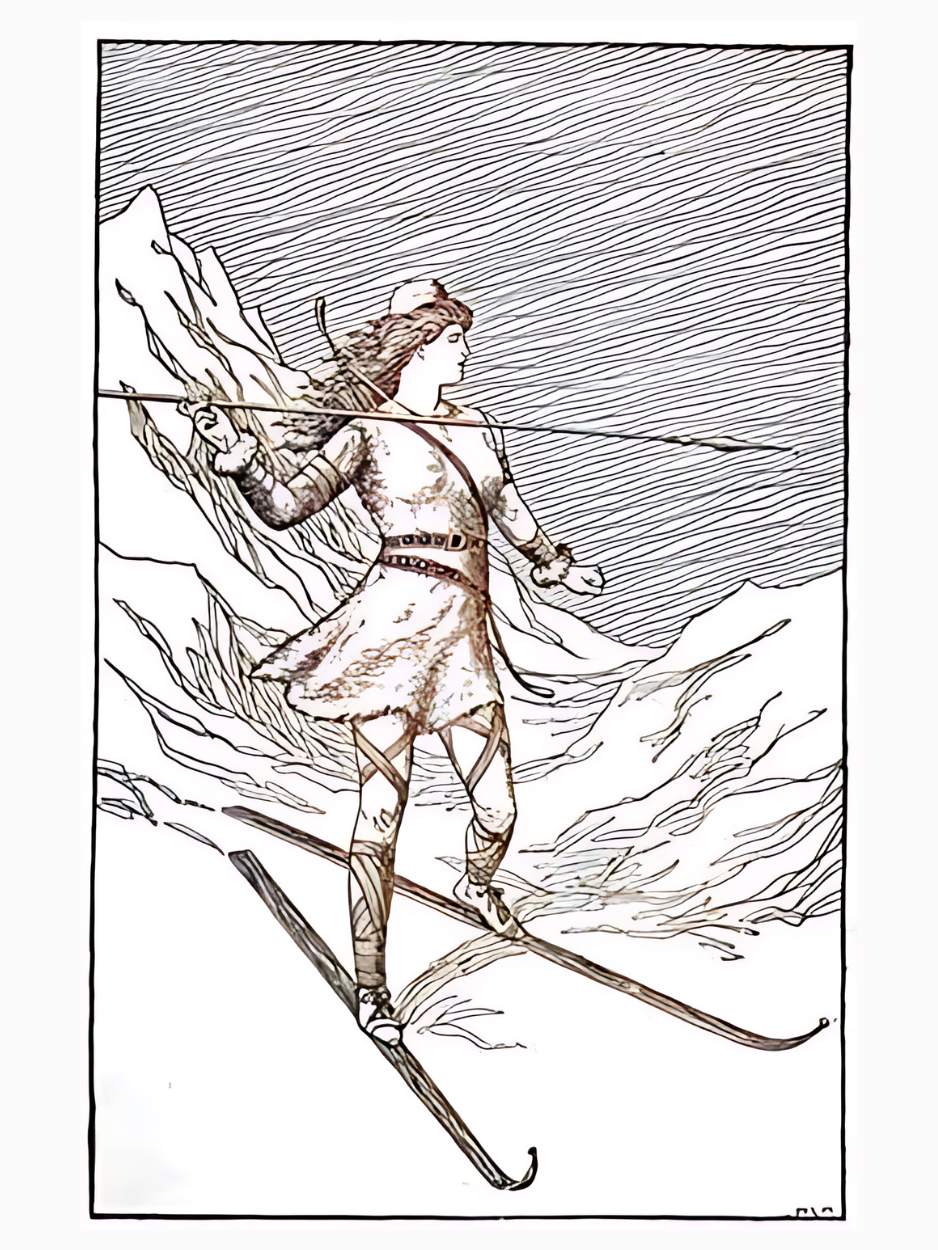

Skaði, the Norse goddess of winter, is a figure with which the Snow Queen shares numerous parallelisms. In the Norse myths, Skaði was the daughter of the giant Thjazi. In the Prose Edda (23) it is said that “she travels on skis, carries a bow and shoots down wild animals. She is called the sky god or the sky lady.” The Snow Queen’s lack of emotion is already attested in Skaði.

In the Skáldskaparmál, also contained in Snorri’s Prose Edda, after the gods had killed his father, Skaði asked for a marriage and for someone to make her laugh as part of her settlement (something which was thought impossible). But Loki managed to do it by tying one end of a cord around the beard of a goat and the other end to his testicles, drawing one another back and forth.

Yes, trickster gods are a weird bunch.

There is another similarity between Andersen’s tale and the Norse myths. In The Snow Queen, two ravens help Gerda during her journey; perhaps an unintentional reference to the pair of ravens that accompany the god Odin and travel throughout the world. Those are called Huginn (Old Norse for “thought”) and Muninn (Old Norse for “memory” or “mind”) and serve Odin as his eyes and will.

Perchta and Holda: German Goddesses

In the Alps regions of Germany and Switzerland, they still remember the winter goddess Perchta (or Bertha). In other areas, there is a similar divinity called Holda (or Holle or Huld or Hulda, perhaps even Huldra in connection with the Scandinavian creature), which is sometimes responsible for the falling of snow. The Perchta goddess is also linked to the Krampus: in her festivities, there are frequently processions of demons with hideous masks named Perchten. Although she is mostly defined as a hideous hunchback crone, sometimes characterized by a long nose, there are links between this figure and Andersen’s Snow Queen, especially in his role of Dame of Winter.

Apart from this connection with winter, Perchta is an educative force for children, another characteristic of the Snow Queen. In some villages, it is believed that the goddess appears to harm children on Christmas Eve and the night before Epiphany, so they have to remain quiet. Sometimes, they are even placed beneath their cradles so she cannot find them. In other places, very much like Santa Claus, she punishes the naughty children and delivers presents for the good ones. The penance is sometimes harsh: she may even open their stomach and fill them with dirt or rubbish. In some areas, Perchta peers into houses and injures those that have lights still on or fires burning late at night. It is also said that Perchta is surrounded by a cohort of infants, those who died before they could have been baptized.

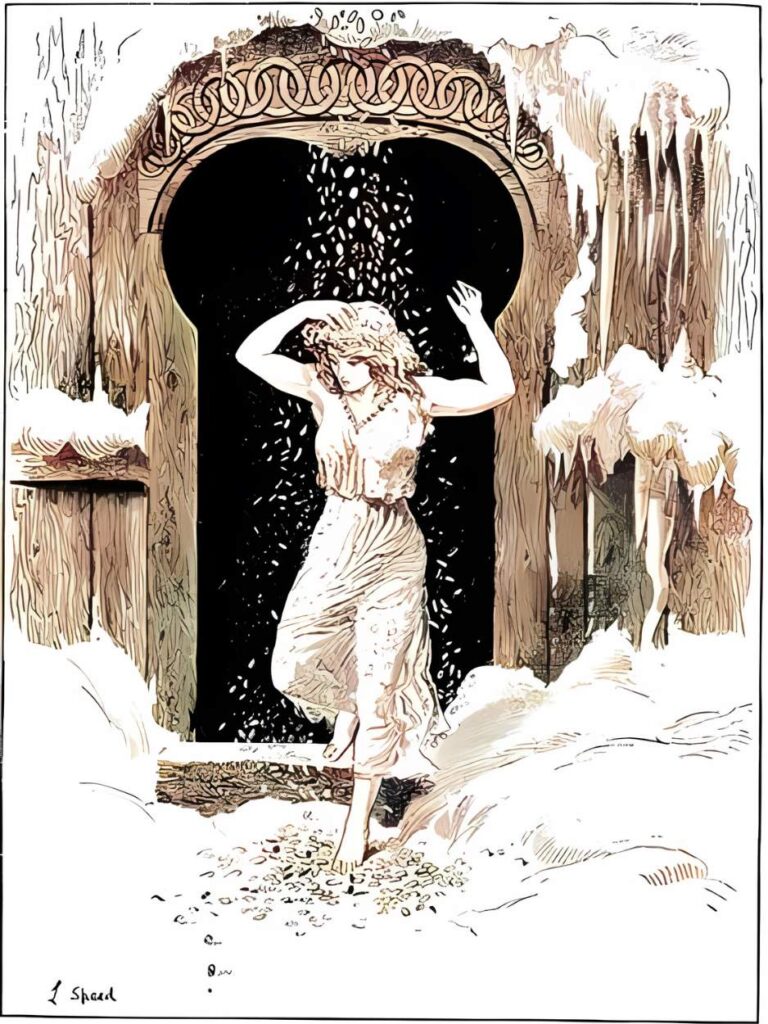

The Frau Holle fairytale: This story was collected by the Grimm brothers. A girl loses a spindle into a well, she leaps into it to get it back and is rescued by Frau Holle and taken to her home. She starts doing housework for her, and the woman insists in her shaking the featherbed pillows every time she makes the bed, because that would make it snow.

You can read it in full here.

Andersen’s possible influences for The Snow Queen

If the figure of the Snow Queen may have come from old Germanic myths, the story itself can be traced back to Ancient Greece. In fact, there are several stories that follow the same pattern as The Snow Queen. In the Aarne–Thompson type, it is classified as 425A, under the name “the search for the lost husband.” Beauty and the Beast and Cupid and Psyche also pertain to this category. Some of them have undoubtedly been known by Andersen by the time he wrote his tale.

A most recent example is Novalis’s Hyacinth and Rosebud (1798). At the beginning of the story, Hyacinth, as Kai, behaves oddly: “He constantly grieved over nothing at all, always went about alone and silent, sat down by himself whenever the others played and were happy, and was always thinking about strange things.” From among the girls, a certain Roseblossom has fallen in love with him. But then comes a wandering man who sits in front of Hyacinth’s house, and he goes out and starts listening to him. He becomes obsessed with his stories, and Roseblossom blames him for them. The vagabond leaves three days later, but by then, Hyacinth has changed, and one day, he declares to his family that he wants to leave and travel to faraway lands, and so he does.

You can read the full story here.

But the main influence for Andersen’s The Snow Queen was probably East of the Sun, West of the Moon, a Norse folktale compiled by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe. On it, a white bear offers a peasant many riches if he offers his youngest daughter in return. The peasant agrees, and the bear takes the girl to a castle. Every night, he removes his skin and turns into a man before going to bed, but he does it with the lights off, so she never has the chance to see him. After a while, the girl gets homesick and wants to visit her family. The bear agrees as long as she does not speak with her mother alone, only when other people are present.

As you can expect, the girl does not fulfill her promise. Her mother tells her that the white bear must be a troll and gives various candles to her so she can light them at night and see the creature (here, if you’re interested in Norse troll transformations). The girl does this, and the next night, she sees a beautiful prince, but because she spills three drops of melted wax on him, she wakes him up. The prince tells her that now he has to go with his evil stepmother, marry a troll princess, and live in the castle east of the sun and west of the moon.

Then, the girl tries to find this place. She asks an old woman, who doesn’t know but gives her an apple, and takes her to a horse, which carries her to another neighbor who has a golden comb. The same thing happens; she gives the comb to her and leads her to another horse that takes her to a third neighbor, this one with a spinning wheel. After this, the girl talks with the East Wind, who has never heard about such a place. Then she goes to the West Wind, then to the South Wind, and finally to the North Wind, which is the only one who knows the castle’s location and is able to take her there.

When in the castle, the girl takes out the apple, and the troll princess wants to buy it from her. As a payment, the girl asks to spend the night in the castle. The troll princess agrees but gives her a sleeping potion to the prince so the girl cannot wake him up. The same happens the second night, and this time, the girl pays the troll princess with the golden comb. The next day, the girl pays with the spinning wheel; this time, however, the prince has been alerted by the town’s folk and does not drink the potion.

The prince declares that he will marry anyone who can clean the candle wax drops from his shirt, knowing that the trolls cannot do it. He calls the girl, who does it, and the trolls flee in rage, and they both finally leave the castle east of the sun and west of the moon.

The Snow Queen-inspired works

There are plenty of works that have taken elements from The Snow Queen. As soon as 1868, famous fairytale Victorian writer George MacDonald started a series named At the Back of the North Wind that ran for three years in a children’s magazine. The protagonist was a child named Diamond, who traveled with the Lady North Wind and lived many adventures.

There are also obvious parallelisms between the Snow Queen and the White Witch from The Chronicles of Narnia, by C. S. Lewis.

This is a description taken from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, originally published in 1950:

“[She was] A great lady, taller than any woman Edmund had ever seen. She was also covered in white fur up to her throat, held a long, straight golden wand in her right hand, and wore a golden crown on her head. Her face was white—not merely pale, but white like snow or paper or icing sugar, except for her very red mouth. It was a beautiful face in other respects, but proud and cold and stern.”

Similarly to the Snow Queen, the White Witch takes Edmund, one of the four children who came to Narnia, in the same way that the Snow Queen takes Kai. Lewis, not particularly keen on the sexual overtones of the original story, makes Edmund follow the White Witch because she promises he will be heir to the throne and because he wants to taste more Turkish Delight sweets. Curiously enough, in the Narnia story, the White Witch is part giantess; perhaps a nod to Skaði, the Norse goddess… or maybe just a coincidence.

More recently, Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy depicts a character who also shares many similarities with the Snow Queen: Marisa Coulter. In fact, some argue that Northern Lights, the first novel in the saga, can be considered a Snow Queen retelling.

The Snow Queen and Frozen

The thought of creating a movie based on The Snow Queen was already being considered by Walt Disney in the Thirties, but the project was finally shelved in 1942. Many ideas and projects were canceled in the early stages of development, but it was not until 2008 that The Snow Queen movie started to be considered seriously again. As told in The Art of Frozen, the episodic character of the tale, as well as its bleak tone, made it difficult for a Disney adaptation. Therefore, the writers moved away from Gerda’s journey and focused their efforts on the story of the Snow Queen.

The first synopsis and suggestions focused on the idea of the Snow Queen as a villain. But the story shifted when they decided to make Elsa and Anna sisters and, especially, when they realized that the famous song Let It Go would never work if the Snow Queen was a pure evil villain. From that point on, the next Frozen script drafts were only loosely based on Andersen’s story.

Despite this, the movie has value as a fairytale retelling. At its heart, the story still shares some strong similarities with the original material. Elsa and Anna are not so different from Kai and Gerda, respectively. Elsa behaves like Kai at the beginning of the movie —albeit for a good reason— and then decides to isolate herself from the outside world; Anna, on the other hand, embarks on a perilous trip to rescue her. The relationship between the two is somewhat similar to the one between the two main characters of The Snow Queen. Elsa and Anna are siblings, true. But Kai and Gerda are described by Andersen in a similar way: “They were not brother and sister,” Andersen writes, “but they were as fond of each other as if they had been.” The relationship between Kai and Gerda is always innocent, as any sexual overtones in the story of The Snow Queen are saved for the Snow Queen character and the robber girl.

The character which shares the most resemblance with the robber girl in Frozen is probably Kristoff. Not a robber, exactly, not a brigand either. He is, however, some kind of an outlaw, even if he is in the “ice business”. He has a reindeer as a mascot and a friend, which connects him with the robber girl, and he develops a romantic relationship with Anna/Gerda.

The “frozen heart,” which in the original tale is a consequence of the mirror shards that the evil troll spreads all over the world, here is a consequence of Elsa’s powers, which I think nicely packs up the story for an animation film. This is, in my opinion, a change for the better; the seven fragments that compose Andersen’s tale are somewhat disconnected and hard to adapt into a movie.

The religious motif, the struggle between reason and faith that stands at the core of Andersen’s story, is lost, too. On the other hand, there is a new struggle between two different worlds and, somehow, between belief systems. The tension in the story between Elsa, whose story is told from a mythic perspective, and Anna, whose story is told from a fairytale perspective, is very interesting as well.

This is a quote from an interview with Thomas Schumacher, the most responsible of Frozen Disney’s Broadway musical:

“What’s interesting about Frozen now is this idea that Anna is living in a fairytale world and Elsa is living in a mythic world. You think about it, and you go, ‘Holy cow!’ I’d like to tell you that was my original thought, but Jennifer Lee pointed that out to me at one point. She said, ‘One of them is in a fairytale, and one of them is in a myth, and these two things have to crash together at the end.’ It’s a big idea to think about.”

This is, to me, an awesome concept, and one I had not noticed until I read this. This connects Elsa with the winter goddess tradition and to the elementary forces of the earth, the seasons, winter… Gerda, on the other side, is a character taken out of a fairytale, looking for her charming prince. The rules of these two different traditions collides, and out of it, conflict arises.