One of the figures that shares the most resemblance to Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen is, unexpectedly, a spirit from Japanese folklore popularly known as Yuki-Onna. As happens with the Snow Queen, Yuki-Onna is a woman who, in some stories, personifies winter. In her most famous depictions, she has black hair, pale skin and a white kimono, and she is portrayed as very beautiful.

This Japanese Snow Queen is a yokai, a word that may mean “monster”, “sprite”, or “demon”. She is known by many names, of which Yuki-Onna is merely one of them. However, all the variations include the word “Yuki” (snow, the kanji character 雪) and then “woman”, “girl”, “crone”, etcetera.

So, in that manner, we have yuki-musume, yukijorō or yuki-onba, but all of them share similar characteristics.

The fact that Japan has its own Snow Queen is not surprising. There are plenty of female figures around the world related with winter and snow. For example, we have Chione (or Kione) in Ancient Greece mythology; and Beira, the Scottish queen of winter in Ireland and Scotland. I’ve also talked before about Skaði, the Norse goddess of winter, and about the Germanic divinities Perchta and Holda.

Even Hawaiian mythology has a goddess of snow: Poli’ahu.

Another one of these characters, Snegurochka, the snow maiden of Russia, arose in importance precisely during the 19th Century, around the time Andersen wrote The Snow Queen and The Ice Maiden. Snegurochka, which is very popular in fairy tales, is an invention from this time with no known roots in ancient folklore.

Yuki-Onna’s first appearance was way before, around the 14th Century, but the best-known story about her was the one written by Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) in Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (by the way, a book that you can get for free here). Kwaidan features a series of ghost stories from Japan, which, in theory, are translations from original Japanese texts. According to the author, the Yuki-Onna story was told to him by a farmer in the Musashi Province, which is, not surprisingly, the region where the action takes place.

The story goes like this:

The Story of Yuki-Onna in Kwaidan: Ghost Stories

In a village of the Mushashi Province there lived two woodcutters: Mosaku, who was an old man, and his apprentice Minokichi, who was barely eighteen. Every day they walked together to the nearby forest to work. For this, they had to get into a ferry to cross a river.

One evening, Mosaku and Minokichi were coming back home when a snowstorm overtook them. When they got to the river they found out that the ferry had left, and so, they had to take shelter in the ferryman’s hut. There were no windows, so they just bolted the door and went to sleep.

Minokichi awoke in the middle of the night when a shower of snow fell over his face. He opened his eyes and saw the door forced open and a woman, all white. She was leaning over Mosaku, blowing her breath over him.

She then turned to Minokichi, who tried to resist but could not, and bent down until her face was very close. The woman was planning to do the same thing to him, but she took pity on Minokichi because he was very young. She decided to spare him but warned him that if he ever told what he had witnessed, she would kill him.

The next morning, Mosaku was dead.

The ferryman came and carried them back to the village, and Minokichi did not say a word to anyone about the white woman that he had seen during the night.

One evening, the next winter, Minokichi was returning home again when he found a girl in the road. She was very beautiful and they started talking. Her name was O-Yuki and she had lost her parents, so she was travelling to Yedo where she expected to get a job as a servant. Minokichi, who by then was charmed by her, asked if she was married. She was not, and he wasn’t either.

When they finally reached the village, O-Yuki stayed at Minokichi’s home, and they soon became husband and wife.

Many years passed, and O-Yuki bore ten children from Minokichi, all with fair skin. But one night, he saw her wife sewing under the candlelight, and he remembered that time in the ferryman’s hut when he started talking about the white woman.

When he finished his story, Minokichi said: “I am not sure if I was dreaming or not, but this is the only time in my life I’ve seen a being as beautiful as you.”

And then O-Yuki shrieked: “It was I, the one you saw! I should kill you right in the spot! But you have ten children now. If you don’t take care of them, I will come back to fulfil my promise, and you will die.”

With these words, she turned into a white mist and disappeared, and she was never seen again.

Other versions of Yuki-Onna

In other stories, Yuki-Onna is not a yokai but a yurei (a ghost). Such is the case of the tale referred to in Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan by Richard Gordon Smith (1918). In it, a farmer called Kyuzaemon receives a spirit visit during a snowstorm. She appears to be the wife of a neighbour who perished in a similar snowstorm the year before, and she comes back for the anniversary of her death. The author concludes: “All those who die by the snow and cold become spirits of snow, appearing when there is snow, just as the spirits of those who are drowned in the sea only appear in stormy seas.”

Some Yuki-Onna stories are particularly interesting for their thematic resonances with Andersen’s Snow Queen. In them, the Yuki-Onna is connected with the presence of children, either coming along with them or harming them. For example, in Niigata Prefecture, it is said that she takes the livers out of children and freezes people to death, but in Tōno, she takes them outside to play during the New Year. There is even one tale in which Yuki-Onna is hugging a child and asking passers-by to do the same. When they hug him, they find out he is becoming heavier and heavier, and finally, they end up covered in snow and freeze to death.

If we take all these stories into account, Yuki-Onna arises as a complex and an ambiguous character, very much like the Snow Queen.

Also, it is important not to confuse Yuki-Onna with Tsurara-Onna, a name which can be loosely translated as “icicle woman”. In some of the Japanese stories about Tsurara-Onna, a man is looking at the icicles that hang under the eaves, thinking how beautiful they are. Then, a woman appears. They get in love and marry soon afterwards. From this point, there are different variations of this tale, but the general idea is that the woman is made of ice and, at some point, it melts or turns back into it. In one version, the woman is cooking in the kitchen, near the fire, and when the man comes, he only finds a wet kimono on the floor. Another possible ending is for her to take a warm bath, with similar consequences. In another story, the Tsurara-Onna disappears with the coming of spring. The man remarries quickly, but the next winter, the woman returns. She becomes so angry that she turns herself into an icicle and stabs the man to death.

The stories about Tsurara-Onna share a similar theme with those of Snegurochka, Russia’s own version of the Snow Queen. As with Yuki-Onna or Tsurara-Onna, there are plenty of different variations of the story. One of the most popular was included in Andrew Lang’s The Pink Fairy Book in 1897.

This is a summary of the story:

Once upon a time, there were a couple of peasants, Ivan and Marie. They could not bear children, and it saddened them. During one winter, they watched a child playing, making a woman of snow, and thought it would be funny to do the same. So they gathered some snow and made a snow child, and as soon as they finished, they found with great surprise that she had come alive.

The couple was very happy with her. They called her Snowflake and led her into their cottage. During the whole winter, she grew and grew until she turned into a thirteen year old girl, and everything was joy and games. But with the coming of spring, Snowflake became sad without reason. She was only happy at dusk and dawn, or every time a storm came.

Spring passed and the eve of St. John came (Midsummer Day), which was a great holiday where girls and boys dance, make fires and jump across them. The girls asked Snowflake to come to the festivities and Marie, though she felt uneasy about the whole thing, agreed.

When the sunset, the girls started to sing songs and dance, and Snowflake did the same. Then they built a fire, formed a row and asked her to repeat what they were going to do. After this, they started to jump across the fire.

Suddenly, they heard a sigh, then a groan, and when they turned around, there was no one there.

They looked for Snowflake everywhere, but she was never to be found again.

Also, if we think about the Frozen movie, we cannot forget Olaf, the snowman that Elsa and Anna created during their childhood. Despite the goofiness of the character, perhaps there is a link between its conception and the tales about the Tsurara-Onna or Snegurochka.

Yuki-Onna today

Today, Yuki-Onna is frequently depicted in movies and manga. For example, she appears in Clamp’s Shirahime-Syo: Snow Goddess Tales and she is one of the characters in Rosario + Vampire by the name of Mizore Shirayuki. In this manga, Yuki-Onna is a race of monsters who, in their true form, have claws made of ice. Mizore can use “cryokinesis”, which means she can freeze any body of water, and she can also create clones from ice, either from herself or from others.

There are many other occurrences of Yuki-Onna in manga and anime. She appears in an episode of Inu Yasha and is a recurring character in Vampire Princess Miyu and Urusei Yatsura. And, of course, the different adaptations of Gegege no Kitaro also depict Yuki-Onna.

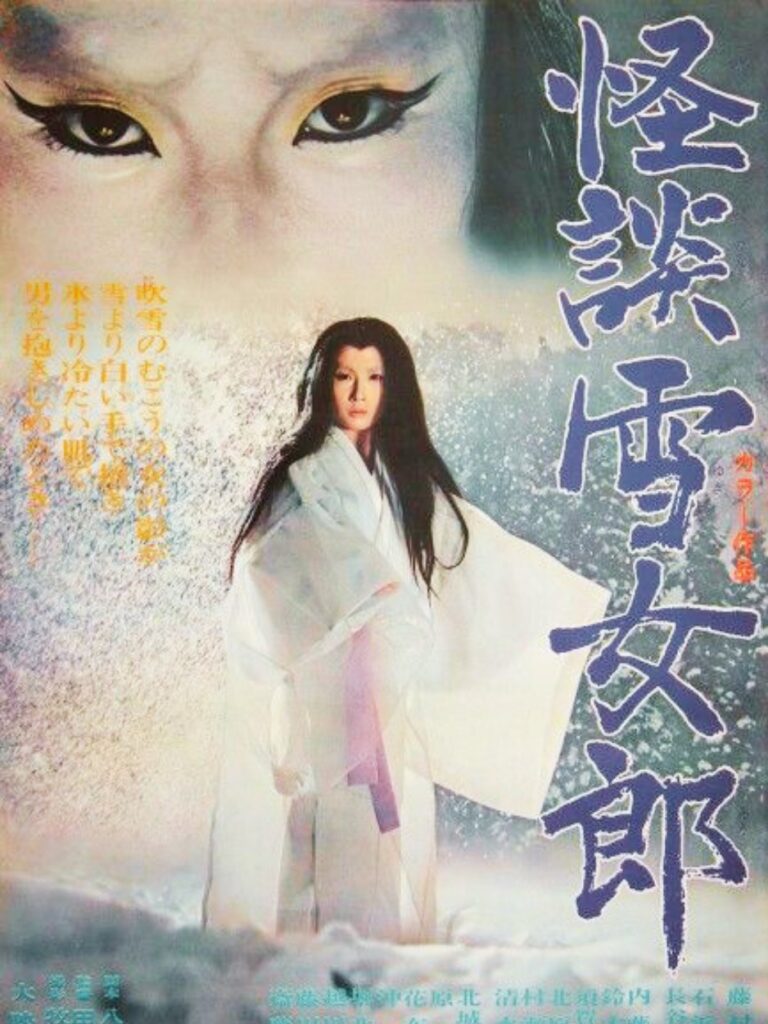

There are also various movies that include Yuki-Onna as a character. The most famous is the adaptation of Kwaidan from 1965 by Masaki Kobayashi, which won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. The second tale of the film is called “The Woman of the Snow”, and it is a retelling of Lafcadio Hearn’s story. Likewise, Yuki-Onna makes an appearance in Dreams, the last film of Akira Kuroshawa, in the segment named “Blizzard”. On it, a man is wandering through a blizzard, and he sees the Yuki-Onna right before he dies. Yuki-Onna is also represented in The Great Yokai War, the 1995 film by Takashi Miike, among many other Japanese spirits and monsters.

A more recent movie was Snow Woman (Yuki-Onna) from 2016 by Kiki Sugino, which is also based on Lafcadio Hearn’s version. Being a whole film devoted to a single tale, it gets into much more detail, though. It is quite interesting how the personality of Yuki-Onna is somehow changed to make a more compelling and multifaceted character. According to Deborah Young’s film’s review in the Hollywood Reporter: “Far from being an evil witch, she seems to use her killing breath almost as euthanasia on ailing bodies that can’t hang on any longer; at least, she lends fate a hand.”